In my last blog I wrote about Rabelo being a people magnet, or at least that she draws a lot of attention at a lock. For this blog I thought I would write about what it takes to drive a 130 ft. barge into a lock that is only four inches wider and three feet longer than Rabelo.

The first thing you have to keep in mind is that Rabelo’s steering station is roughly 100 feet back from the bow. Imagine the nose of your car a 100 feet ahead of you and only two inches on each side of the garage to get in. Rabelo weighs 240 tons, so her weight is another major factor. Our big baby does not stop on a dime. In fact she won’t even stop on a football field.

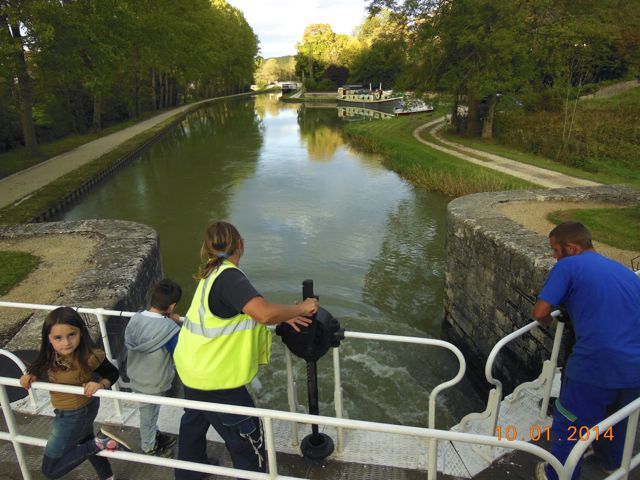

As I approach a lock, at around 300 meters or roughly 1,000 feet, I have to begin slowing Rabelo down. It’s best not to place the engine into neutral or even idle as the rudder becomes very inefficient, which makes Rabelo difficult to steer. It takes water flowing past the rudder to provide steering, and it is best if that water comes from the turning propeller. When I am about 300 feet from the lock I begin lining Rabelo up to enter the lock. I use a lot of visual clues to do this. The first things I look at are the lock walls. If I can see more of one wall than the other then I know I have to move Rabelo over until both walls appear even. The closer Rabelo gets to the lock the finer the adjustments are. When I am about one boat length from the lock I have to make sure that Rabelo is approaching the lock exactly parallel to its walls and the bow is lined up to enter the lock.

“Approaching a lock. Note how the wall on the right is slightly more visible. Rabelo will need to move to the right.”

This is where Julian has been a big help, as he instituted what we call counting. Julian will sit on the edge of the boat just outside the pilothouse and tell me if Rabelo is lined up perfectly or if the stern needs to be moved over. Remember that if I move the stern then I will first need to move the bow even though it may be lined up perfectly. Once the stern is where it is supposed to be then I can put the bow back where it belongs. It’s a bit of a balancing act, but after five or six hundred locks you get the hang of it. As Rabelo continues to close in on the lock at around one mile per hour Julian will start calling out numbers. He might start with something like plus four, which means there are four inches of clearance between Rabelo’s side and the lock wall. That’s too much. I’d have to move the bow over three inches. If Julian tells me negative four then I have to move the bow five inches in the opposite direction. When Julian announces plus one that means I’m lined up perfectly with one inch of clearance.

Hopefully with Julian’s help I have placed Rabelo exactly where she is supposed to be, and we begin entering the lock without a bump. Once Rabelo is about a third of the way into the lock I no longer have to worry about steering. My only concern is getting her situated in the lock so that the bow is as close to the lock doors as possible. Most of that responsibility will fall on Julian. He will run up to the bow, place the bow line over a bollard on shore and wrap it around the two bollards on Rabelo’s bow. Then he will begin slowing Rabelo down even further by adding tension to the line. If we are going up in a lock then we will place the bow about two inches from the concrete ledge just in front of the lock doors. If we are going down then Julian will stop us about six to eight inches from the lock doors. All this time I have kept Rabelo’s engine in forward to keep tension on the bow line. Once Rabelo is stopped I run outside and drop the stern line over a bollard on shore. Then I wrap it around the two bollards next to the pilothouse, and tie up the stern. I then run back into the pilothouse, place the engine in neutral, and turn the rudder ninety degrees. We can’t leave Rabelo’s rudder straight as it hangs out too far and we would run the risk of damaging it. Also when we tie up inside a lock we can’t have any slack in our lines, as Rabelo will move around too much when the water level begins to change. That could possibly damage the lock or even worse damage our rudder.

Once we are tied up we can begin to operate the lock. The French locks have many different systems some are automated and others are completely manual. When we are in a manually operated lock there is a VNF employee to operate it. In the manual locks we always help out the VNF guy or girl open and close the lock doors.

As the lock begins to fill or empty Julian and I have to adjust the lines to take up the slack. When the lock has filled or emptied it is time to leave. The lock doors are opened and, the bow line is always removed first. I place the engine in forward and as soon as we begin to move I will run outside and take the stern line off. The reason we wait until Rabelo is moving forward is because there have been a few occasions when we were in a lock and a wave of water caused by the emptying of a lock further up the canal has pushed us back into the lock gate.

I’ve actually shortened the procedure, and simplified it, but you get the idea. It may sound like a lot, but after a few hundred locks it starts to become second nature. It’s a challenge driving Rabelo, but it’s something I enjoy. For this blog I didn’t bother to write about what happens when there is a cross wind or a current. All I will say is that if there is a cross wind or current things can get very exciting.

-Tom Miller

Author of “The Wave” and “When Stones Speak”– Chuck Palmer Adventure novels

DEC

About the Author:

Tom Miller graduated from the University of Southern California with a Bachelor of Science in Geology. He is a consummate adventurer with over 1,000 dives as a recreational scuba diver, and an avid sailor who has traveled 65,000 miles throughout the Pacific including the Hawaiian Islands. Miller has also cruised the canals of Europe on his canal barge and given numerous lectures on cruising the canals of Europe, as well as sailing in the South Pacific. Piloting is also an interest of Miller's, and He has completed over 1,000 hours flying everything from small Cessnas to Lear jets.